ARTÍCULO

The upper reaches of the largest river in Southern China as an “evolutionary front” of tropical plants: Evidences from Asia-endemic genus Hiptage (Malpighiaceae)

M.-X. REN (任明迅)1,2

1 Key Laboratory of Protection and Development Utilization of Tropical Crop Germplasm Resources (Hainan University),

Ministry of Education, CN-570228 Haikou, China

2 College of Horticulture and Landscape Architecture, Hainan University, CN-570228 Haikou, China

Author for correspondence: M.-X. Ren (rensanshan@hotmail.com)

Editors: J.-Q. Liu & N. Garcia-Jacas

ABSTRACT

The upper reaches of the largest river in southern China as an “evolutionary front” of tropical plants: evidences from asia-endemic genus Hiptage (Malpighiaceae).— The biodiversity hotspot at the Guizhou–Yunnan–Guangxi borders is a distribution centre of tropical plants in China. It spans the whole upper reaches of Zhujiang River, the largest river in Southern China. In this paper, I aimed to explore the roles of the river in the spread and diversification of tropical plants in this area, using the Asia-endemic genus Hiptage Gaertn. (Malpighiaceae) as an example. Two diversity and endemism centres of Hiptage are recognized: Indo-China Peninsula and upper reaches of Zhujiang River (UZJ). The area-adjusted endemism index further indicates UZJ as the most important distribution region of endemic species since UZJ has a very small area (~210,000 km2) but six out of the total seven species are narrow endemics. UZJ is located at the northern edge of distribution ranges of Hiptage, which resulted mainly from the north-west–south-east river systems of UZJ promoting northward spreads of this tropical genus. The highly-fragmented limestone landscapes in this region may promote habitat isolation and tends to be the main driving factor for origins of these endemic species. Hiptage is also distinctive for its highly-specialized pollination system, mirror-image flowers, which probably facilitates species diversification via floral and pollination isolation. Other studies also found UZJ as a major diversification centre of the tropical plant families Gesneriaceae and Begoniaceae. Thereafter, it is concluded that UZJ is an “evolutionary front” of tropical plants in China, which contributes significantly to the origin and maintenance of the unique biodiversity in the area.

KEYWORDS: adaptation; biodiversity; endemic plant; endemism centre; karst; mirror-image flowers; pollination; speciation.

El curso superior del río más grande del sur de china como un «frente evolutivo» de plantas tropicales: evidencia del género endémico de Asia Hiptage (Malpighiaceae)

RESUMEN

El curso superior del río más grande del sur de china como un «frente evolutivo» de plantas tropicales: evidencia del género endémico de Asia Hiptage (Malpighiaceae). — El hotspot de biodiversidad en las fronteras de las provincias Guizhou-Yunnan-Guangxi es un centro de distribución de plantas tropicales en China. Se extiende por toda la cuenca alta del río Zhujiang, el mayor río del sur de China. En este artículo, se explora el papel del río en la propagación y la diversificación de las plantas tropicales en este área, usando el género endémico de Asia Hiptage Gaertn.(Malpighiaceae) como ejemplo. Se reconocen dos centros de diversidad y endemismo de Hiptage: la Península Indochina y el curso superior del río Zhujiang (UZJ). El índice de endemismo ajustado al área indica UZJ como la región más importante de distribución de especies endémicas, ya que, aunque UZJ tiene un área muy pequeña (~210.000 km2), seis de un total de siete especies son estrictamente endémicas. UZJ está situado en el extremo norte del área de distribución de Hiptage, lo que resultó principalmente de la disposición noroeste-sureste de los sistemas fluviales de UZJ, que facilitaron la expansión y diferenciación hacia el norte de este género tropical. Los paisajes de piedra caliza altamente fragmentados en esta región han contribuido al aislamiento de hábitat y pueden ser el principal factor para el origen de estas especies endémicas. Hiptage también se distingue por su sistema de polinización altamente especializado, con flores de imagen especular, lo que probablemente facilita la diversificación de las especies a través del aislamiento de la polinización. Otros estudios también encontraron que UZJ es un importante centro de diversificación de las familias de plantas tropicales Begoniaceae y Gesneriaceae. Por consiguiente, se concluye que UZJ es un «frente evolutivo» de plantas tropicales en China, lo que contribuye de manera significativa al origen y mantenimiento de la biodiversidad única en la zona.

PALABRAS CLAVE: adaptación; biodiversidad; centro de endemismo; especiación; flores de imagen especular; karst; planta endémica; polinización.

摘要

南中国最大河流珠江的上游地区是热带植物的一个“进化前沿”:来自金虎尾科亚洲特有属风筝果属(Hiptage)的证据。— 中国西南的云南-贵州-广西交界区是全球性的生物多样性热点地区,也是中国热带植物的分布中心。这一区域横跨南中国最大河流—珠江的整个上游地区。这里,我试图以典型的热带植物类群金虎尾科 (Malpighiaceae) 亚洲特有的风筝果属(Hiptage Gaertn.)为例,从河流的作用来解释这一地区热带植物的扩散与物种分化及其生物多样性热点地区的形成。风筝果属具有两个物种多样性与特有中心:一个位于中南半岛南部,一个则是珠江上游地区。面积校正后的特有性指数进一步证实,珠江上游地区是风筝果属最集中的特有种分布地区,其大约210,000 km2的面积上有7个种,其中6个为狭域分布的地方特有种。珠江上游地区位于风筝果属整个分布区域的北缘;风筝果属植物能扩散到这一地区,主要得益于该地的河流走向基本都呈西北-东南走向。西北-东南走向的河道可以促进东南亚暖湿气流北进,从而允许风筝果属等热带植物得以扩散至珠江上游地区的红水河、南盘江以及右江等地。这些地方分布着高度破碎化的岩溶地貌,又进一步促进了局部生境隔离与物种分化。此外,风筝果属还具有极其特化的传粉系统“镜像花柱”(mirror-image flowers),可能加速了繁殖隔离与物种分化。其它研究也发现,珠江上游地区是一些典型热带植物类群如苦苣苔科和秋海棠科的物种多样化中心。因此,珠江上游地区(滇黔桂交界区)很可能就是中国热带植物的一个“进化前沿”,对这一地区独特生物多样性的形成与维持具有重要作用。

关键词:生物多样性;特有植物;特有中心;适应;岩溶地貌;镜像花柱;传粉;物种形成。

Recibido: 28/10/2014 / Aceptado: 16/12/2014

Cómo citar este artículo / Citation: Ren, M.-X. 2015. The upper reaches of the largest river in Southern China as an “evolutionary front” of tropical plants: Evidences from Asia-endemic genus Hiptage (Malpighiaceae). Collectanea Botanica 34: e003. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.3989/collectbot.2015.v34.003

Copyright: © 2015 Institut Botànic de Barcelona (CSIC). Este es un artículo de acceso abierto distribuido bajo los términos de la licencia Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial (by-nc) Spain 3.0. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial (by-nc) Spain 3.0 License.

CONTENIDOS

INTRODUCTIONTop

China is one of the richest countries in plant biodiversity, harbouring more than 30,000 seed plants (Liu et al., 2003Liu, J., Ouyang, Z., Pimm, S. L., Raven, P. H., Wang, X., Miao, H. & Han, N. 2003. Protecting China’s biodiversity. Science 300: 1240–1241. http://dx.doi.org/10.1126/science.1078868; López-Pujol et al., 2006López-Pujol, J., Zhang, F.-M & Ge, S. 2006. Plant biodiversity in China: richly varied, endangered, and in need of conservation. Biodiversity and Conservation 15: 3983–4026. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10531-005-3015-2). Such “mega-biodiversity” (Mittermeier et al., 1997Mittermeier, R. A., Gil, P. R. & Mittermeier, C. G. 1997. Megadiversity: Earth’s biologically wealthiest nations. Conservation International (CI), Washington, DC.; Liu et al., 2003Liu, J., Ouyang, Z., Pimm, S. L., Raven, P. H., Wang, X., Miao, H. & Han, N. 2003. Protecting China’s biodiversity. Science 300: 1240–1241. http://dx.doi.org/10.1126/science.1078868; Tang et al., 2006Tang, Z., Wang, Z., Zheng, C. & Fang, J. 2006. Biodiversity in China’s mountains. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment 4: 347–352. http://dx.doi.org/10.1890/1540-9295(2006)004[0347:bicm]2.0.co;2) has been often attributed to the highly complicated ecological and evolutionary history of China and East Asia. For example, China has complex topographies and almost all types of biomes from tropical to boreal, which provides abundant suitable habitats for various plants (Ying, 2001Ying, T.-S. 2001. 中国种子植物物种多样性及其分布格局 [Species diversity and distribution pattern of seed plant in China]. Biodiversity Science 9: 393–398 [in Chinese].). China is also one of major centres of origin and diversification for vascular plants (Axelrod et al., 1996Axelrod, D. I., Al-Shehbaz, I. & Raven, P. H. 1996. History of the modern flora of China. In: Zhang, A. & Wu, S. (Eds.), Floristic characteristics and diversity of East Asian plants. China Higher Education Press, Beijing: 43–55.; Qian, 2002Qian, H. 2002. A comparison of the taxonomic richness of temperate plants in East Asia and North America. American Journal of Botany 89: 1818–1825. http://dx.doi.org/10.3732/ajb.89.11.1818, and particularly the southern part of this vast country is the home for both relict and recently evolved plants (Ying & Zhang, 1984Ying, T.-S. & Zhang, Z.-S. 1984. 中国植物区系中的特有现象–特有属的研究 [Endemism in the flora of China – Studies on the endemic genera]. Acta Phytotaxonomica Sinica 22: 259–268 [in Chinese].; López-Pujol et al., 2011López-Pujol, J., Zhang, F.-M, Sun, H.-Q., Ying, T.-S. & Ge, S. 2011. Centres of plant endemism in China: places for survival or for speciation? Journal of Biogeography 38: 1267–1280. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2699.2011.02504.x).

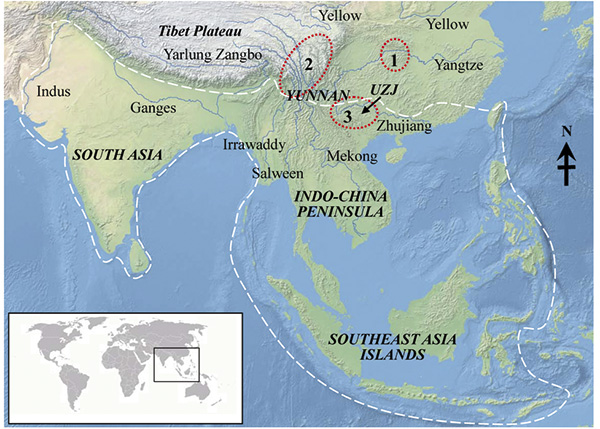

In Southern China, three regions are widely recognized as major “biodiversity hotspots” and they are roughly equal to the country’s “centres of plant endemism” (Ying & Zhang, 1984Ying, T.-S. & Zhang, Z.-S. 1984. 中国植物区系中的特有现象–特有属的研究 [Endemism in the flora of China – Studies on the endemic genera]. Acta Phytotaxonomica Sinica 22: 259–268 [in Chinese].; Ying et al., 1993Ying, T. S, Zhang, Y. L. & Boufford, D. E. 1993. The endemic genera of seed plants in China. Science Press, Beijing.; Ying, 1996Ying, T.-S. 1996. 中国种子植物特有属的分布区学研究 [Aerography of the endemic genera of seed plants in China]. Acta Phytotaxonomica Sinica 34: 479–485 [in Chinese].; López-Pujol et al., 2011López-Pujol, J., Zhang, F.-M, Sun, H.-Q., Ying, T.-S. & Ge, S. 2011. Centres of plant endemism in China: places for survival or for speciation? Journal of Biogeography 38: 1267–1280. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2699.2011.02504.x). All these three hotspots are located in mountain areas with large rivers (Fig. 1) but they differ significantly in plant composition and origin. The biodiversity hotspot at central China locates at the boundaries of Hubei, Hunan, and Guizhou provinces, and Chongqing City, including the Three Gorges region on the Yangtze River (Fig. 1). Most endemic plants in this region are palaeoendemics, i.e. the relict species that have survived from the Tertiary (Ying et al., 1993Ying, T. S, Zhang, Y. L. & Boufford, D. E. 1993. The endemic genera of seed plants in China. Science Press, Beijing.; López-Pujol et al., 2011López-Pujol, J., Zhang, F.-M, Sun, H.-Q., Ying, T.-S. & Ge, S. 2011. Centres of plant endemism in China: places for survival or for speciation? Journal of Biogeography 38: 1267–1280. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2699.2011.02504.x). The Hengduan Mountains on the eastern fringe of the Tibetan Plateau are also widely recognized as a globally important biodiversity hotspot. It consists largely of recently evolved endemic species (neoendemics) that resulted from the uplift of the Himalayas and surrounding mountains (Chapman & Wang, 2002Chapman, G. P. & Wang, Y. Z. 2002. The plant life of China. Diversity and distribution. Springer-Verlag, Berlin & Heidelberg. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/978-3-662-04838-2; Qian, 2002Qian, H. 2002. A comparison of the taxonomic richness of temperate plants in East Asia and North America. American Journal of Botany 89: 1818–1825. http://dx.doi.org/10.3732/ajb.89.11.1818). The third hotspot spans the upper reaches of Zhujiang River (the largest river in Southern China), at the confluence of three Chinese provinces (Guizhou, Yunnan, and Guangxi). This biodiversity hotspot (hereafter UZJ) is dominated by limestone landscapes and river valleys (Figs. 1 and 2). UZJ is also distinctive for its nearly equal proportion of neoendemics and palaeoendemics (Ying et al., 1993Ying, T. S, Zhang, Y. L. & Boufford, D. E. 1993. The endemic genera of seed plants in China. Science Press, Beijing.; López-Pujol et al., 2011López-Pujol, J., Zhang, F.-M, Sun, H.-Q., Ying, T.-S. & Ge, S. 2011. Centres of plant endemism in China: places for survival or for speciation? Journal of Biogeography 38: 1267–1280. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2699.2011.02504.x) and significantly more tropical species than the other two hotspots. Myers et al. (2000Myers, N., Mittermeier, R. A., Mittermeier, C. G., da Fonseca, G. A. B, & Kent, J. 2000. Biodiversity hotspots for conservation priorities. Nature 403: 853–858. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/35002501) included it as one part of the globally important biodiversity hotspot “Indo-Burma”. Compared to other hotspots, UZJ hotspot received less attention, and the evolutionary histories and maintenance mechanisms of its unusual biodiversity have not been satisfactorily resolved (Ying et al., 1993Ying, T. S, Zhang, Y. L. & Boufford, D. E. 1993. The endemic genera of seed plants in China. Science Press, Beijing.; Fang et al., 1995Fang, R.-Z., Bai, P.-Y., Huang G.-B. & Wei Y.-G. 1995. 滇黔桂热带亚热带 (滇黔桂地区和北部湾地区) 种子植物区系 [A floristic study on the seed plants from tropics and subtropics of Dian-Qian-Gui]. Acta Botanica Yunnanica S7: 111–150 [in Chinese].).

|

Figure 1. Distribution of the genus Hiptage and the associated important geographic regions. The white line indicates the distribution range of Hiptage, which was divided into five regions with their names in bold and italics. The red dash-lined circles are the three biodiversity hotspots in China: 1, borders of Hubei–Hunan–Guizhou–Chongqing, including Three Gorges Region on the Yangtze River; 2, Hengduan Mountains; 3, borders of Guizhou–Yunnan–Guangxi, roughly equal to the upper reaches of Zhujiang River (UZJ). The background map was provided by Dr. J. López-Pujol.

[View full size] [Descargar tamaño completo] |

|

In this paper, I will use the distribution map of Hiptage, an Asia-endemic genus of the typically tropical family Malpighiaceae, with the aims of: (1) to determine the diversity and endemism centre(s) of the genus by calculating species richness and endemism for five different geographic regions; (2) to discuss possible determinants for distribution patterns of Hiptage from both environmental and biological factors by comparing widely-recognized hypothesis and updated studies on this genus; (3) to explore the underlying mechanism(s) of origin and maintenance of the tropical plant diversity in UZJ hotspot with an emphasis on the roles of river and associated environmental features.

MATERIALS AND METHODSTop

Basic information of the genus Hiptage

Hiptage is one of the largest Old World genera of Malpighiaceae, with >25 species usually recognized (Anderson et al., 2006Anderson, W. R., Anderson, C. & Davis, C. C. 2006–. Malpighiaceae. University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. Retrieved September 10, 2014 from http://herbarium.lsa.umich.edu/malpigh/index.html–). This genus is originated as a result of inter-continent long-distance dispersals from tropical America to Asia during the late Oligocene, ~29 Ma (Davis et al., 2002Davis, C. C., Bell, C. D., Mathews, S. & Donoghue, M. J. 2002. Laurasian migration explains Gondwanan disjunctions: evidence from Malpighiaceae. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 99: 6833–6837. http://dx.doi.org/10.1073/pnas.102175899).

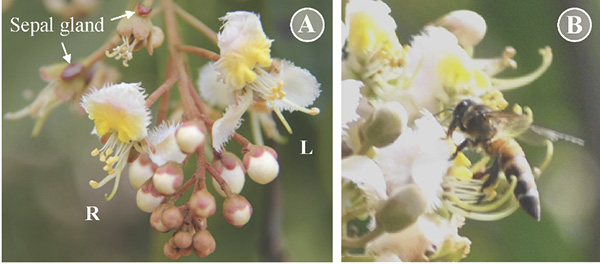

Hiptage species grows mainly as high-climbing, twining woody lianas in South Asia, Indo-China Peninsula, Indonesia, Philippines, and Southern China including Hainan and Taiwan islands (Chen & Funston, 2008Chen, S. & Funston, A. M. 2008. Malpighiaceae. In: Wu, Z. Y., Raven, P. H. & Hong, D. Y. (Eds.), Flora of China 11 (Oxalidaceae through Aceraceae). Science Press, Beijing & Missouri Botanical Garden Press, St. Louis: 132–138.; Ren et al., 2013Ren, M.-X., Zhong, Y.-F. & Song, X.-Q. 2013. Mirror-image flowers without buzz pollination in the Asia-endemic Hiptage benghalensis (Malpighiaceae). Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society 173: 764 –774. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/boj.12101). Jacobs (1955Jacobs, M. 1955. Malpighiaceae. In: Steenis, C. G. G. J. van (Ed.), Flora Malesiana Ser. 1, 5(2). Noordhoff-Kolff, Djakarta: 125–145.) also reported one endemic species in Fiji islands, which locates at Southern Pacific. Because of its three-winged peculiar samara, Hiptage is probably the Old World genus easiest to recognize. Its flowers are bilaterally symmetrical and basically white but the posterior petal is often yellow in its centre (Fig. 3A). The number and structure of sepal gland(s) represent diagnostic traits in the family (Jacobs, 1955Jacobs, M. 1955. Malpighiaceae. In: Steenis, C. G. G. J. van (Ed.), Flora Malesiana Ser. 1, 5(2). Noordhoff-Kolff, Djakarta: 125–145.; Anderson, 1990Anderson, W. R. 1990. The origin of the Malpighiaceae—the evidence from morphology. Memoirs of the New York Botanical Garden 64: 210–224.; Vogel, 1990Vogel, S. 1990. History of the Malpighiaceae in the light of pollination ecology. Memoirs of the New York Botanical Garden 55: 130–142.; Srivastava, 1992Srivastava, R. C. 1992. Taxonomic revision of the genus Hiptage Gaerlner (Malpighiaceae) in India. Candollea 47: 601–612.; Chen & Funston, 2008Chen, S. & Funston, A. M. 2008. Malpighiaceae. In: Wu, Z. Y., Raven, P. H. & Hong, D. Y. (Eds.), Flora of China 11 (Oxalidaceae through Aceraceae). Science Press, Beijing & Missouri Botanical Garden Press, St. Louis: 132–138.). Normally only the posterior sepal bearing one large gland in Hiptage but in some species gland is missing or borne in pairs (Vogel, 1990Vogel, S. 1990. History of the Malpighiaceae in the light of pollination ecology. Memoirs of the New York Botanical Garden 55: 130–142.; Anderson et al., 2006Anderson, W. R., Anderson, C. & Davis, C. C. 2006–. Malpighiaceae. University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. Retrieved September 10, 2014 from http://herbarium.lsa.umich.edu/malpigh/index.html–; Chen & Funston, 2008Chen, S. & Funston, A. M. 2008. Malpighiaceae. In: Wu, Z. Y., Raven, P. H. & Hong, D. Y. (Eds.), Flora of China 11 (Oxalidaceae through Aceraceae). Science Press, Beijing & Missouri Botanical Garden Press, St. Louis: 132–138.). Stamens are 10, one of them much longer and bigger than the other nine. All anthers of Hiptage dehisce longitudinally (Ren et al., 2013Ren, M.-X., Zhong, Y.-F. & Song, X.-Q. 2013. Mirror-image flowers without buzz pollination in the Asia-endemic Hiptage benghalensis (Malpighiaceae). Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society 173: 764 –774. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/boj.12101), contrasting to poricidal anthers in most heteromorphic stamens. Ren et al. (2013Ren, M.-X., Zhong, Y.-F. & Song, X.-Q. 2013. Mirror-image flowers without buzz pollination in the Asia-endemic Hiptage benghalensis (Malpighiaceae). Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society 173: 764 –774. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/boj.12101) found in H. benghalensis (L.) Kurz, the most widespread species of the genus, that longitudinal anthers probably are an adaptation to its pollinator Apis dorsata, an Asia-endemic pollen-collecting honeybee (Fig. 3B).

Hiptage is also distinctive for having mirror-image flowers (Ren et al., 2013Ren, M.-X., Zhong, Y.-F. & Song, X.-Q. 2013. Mirror-image flowers without buzz pollination in the Asia-endemic Hiptage benghalensis (Malpighiaceae). Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society 173: 764 –774. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/boj.12101). Mirror-image flowers show a sexual polymorphism in which the style deflects either to the left (left-styled flower) or the right (right-styled flower) side of the floral axis, and the bigger stamen deflects to the opposite side of the style (Fig. 3A). Normally insects enter the flower between the style and the big stamen and consequently contact two sexual organs respectively with their left and right side of abdomens (Fig. 3B; Jesson & Barrett, 2002Jesson, L. K. & Barrett, S. C. H. 2002. Enantiostyly: solving the puzzle of mirror-image flowers. Nature 417: 707. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/417707a; Ren et al., 2013Ren, M.-X., Zhong, Y.-F. & Song, X.-Q. 2013. Mirror-image flowers without buzz pollination in the Asia-endemic Hiptage benghalensis (Malpighiaceae). Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society 173: 764 –774. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/boj.12101). Therefore, mirror-image flowers exhibit a highly specialized insect-pollinating mechanism for promoting cross-pollination between left- and right-styled flowers or reducing pollination between flowers on the same plant (Barrett et al., 2000Barrett, S. C. H., Jesson, L. K. & Baker, A. M. 2000. The evolution and function of stylar polymorphisms in flowering plants. Annals of Botany 85: 253–265. http://dx.doi.org/10.1006/anbo.1999.1067; Jesson & Barrett, 2002Jesson, L. K. & Barrett, S. C. H. 2002. Enantiostyly: solving the puzzle of mirror-image flowers. Nature 417: 707. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/417707a; Ren et al., 2013Ren, M.-X., Zhong, Y.-F. & Song, X.-Q. 2013. Mirror-image flowers without buzz pollination in the Asia-endemic Hiptage benghalensis (Malpighiaceae). Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society 173: 764 –774. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/boj.12101).

|

Figure 3. Mirror-image flowers (A) and its main pollinator Apis dorsata (B) of Hiptage benghalensis, the most widespread species of the genus. L, left-styled flower; R, right-styled flower. The sepal gland is indicated by arrows.

[View full size] [Descargar tamaño completo] |

|

Species identification

Published floras including Flora of China (Chen & Funston, 2008Chen, S. & Funston, A. M. 2008. Malpighiaceae. In: Wu, Z. Y., Raven, P. H. & Hong, D. Y. (Eds.), Flora of China 11 (Oxalidaceae through Aceraceae). Science Press, Beijing & Missouri Botanical Garden Press, St. Louis: 132–138.), Flora of Thailand (Sirirugsa, 1991Sirirugsa, P. 1991. Malpighiaceae. In: Smitinand, T. & Larsen, K. (Eds.), Flora of Thailand 5(3). The Forest Herbarium, Royal Forest Department, Bangkok: 272–299.), Flora of Malaysia (Jacobs, 1955Jacobs, M. 1955. Malpighiaceae. In: Steenis, C. G. G. J. van (Ed.), Flora Malesiana Ser. 1, 5(2). Noordhoff-Kolff, Djakarta: 125–145.), Flora of Bhutan (Grierson, 1991Grierson, A. J. C. 1991. Malpighiaceae. In: Grierson, A. J. C. & Long, D. G. (Eds.), Flora of Bhutan 2(1). Royal Botanic Garden, Edinburgh: 40–42.), and Flora of Taiwan (Chen, 1993Chen, C. H. 1993. Malpighiaceae. In: Huang, T. C. (Ed.), Flora of Taiwan 3 (2nd ed.). Lunwei Printing Company, Taipei: 565–566.) were used to identify Hiptage species and their geographic distributions. Hiptage species in India were mainly determined according to Srivastava (1992Srivastava, R. C. 1992. Taxonomic revision of the genus Hiptage Gaerlner (Malpighiaceae) in India. Candollea 47: 601–612.). All the described species in these floras were checked. The Malpighiaceae website http://herbarium.lsa.umich.edu/malpigh/ (Anderson et al., 2006Anderson, W. R., Anderson, C. & Davis, C. C. 2006–. Malpighiaceae. University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. Retrieved September 10, 2014 from http://herbarium.lsa.umich.edu/malpigh/index.html–) was also used as a guideline. When there was any mismatching information about taxonomy and distribution, I referred to the newest floras. Finally, 29 species were recognized in this study (Appendix).

Distribution regions

According to geographic locations and landscape type, the distribution range of Hiptage was classified into five geographic regions: Islands (Philippines, Indonesia, Fiji, Andaman); South Asia (Pakistan, Sri Lanka, Bhutan, Nepal, Bengal, India); Indo-China Peninsula (including Malay Peninsula); upper reaches of Zhujiang River (UZJ); and Yunnan Province (except the area included into UZJ). Yunnan Province was analysed separately because this province is the major distribution centre of tropical plants in China (Zhu et al., 2003Zhu, H., Wang, H., Li, B. & Sirirugsa, P. 2003. Biogeography and floristic affinities of the limestone flora in southern Yunnan, China. Annals of Missouri Botanical Garden 90: 444–465. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/3298536). The area occupied by the different regions varies greatly, ranging from a minimum of 21 × 104 km2 in UZJ to a maximum of 410 × 104 km2 in South Asia (Table 1).

| Table 1. Geographic distribution patterns of Hiptage species. Two diversity and endemism centres are indicated in bold. NT is species richness (the number of total species); SD (species density) = NT/[ln(area) + ln(elevation range)]; NE is the number of endemic species; EI (endemism index) = [NE/(NT − NE)]/[ln(area) + ln(elevation range)]. |

|

Region

|

Distance to the equator (km)

|

Area (× 104 km2)

|

Elevation range (m)1

|

NT

|

SD

|

NE

|

EI

|

|

Islands (Philippines, Fiji, Indonesia, Andaman)

|

0–2100

|

220

|

2000

|

8

|

0.62

|

4

|

0.08

|

|

Indo-China Peninsula

|

130–2500

|

230

|

5880

|

16

|

1.13

|

10

|

0.12

|

|

Upper reaches of Zhujiang River (UZJ)

|

2500–2800

|

21

|

2400

|

7

|

0.65

|

6

|

0.55

|

|

Yunnan Province (except UZJ)

|

2300–3200

|

30

|

6600

|

4

|

0.33

|

1

|

0.03

|

|

South Asia (Sri Lanka, India, Bengal, Pakistan)

|

600–3800

|

410

|

1500

|

8

|

0.60

|

2

|

0.03

|

|

1 Elevation range is calculated as the difference between highest and lowest elevation of the region, which is used to estimate habitat heterogeneity.

|

|

Excepting the islands region, all the other four regions were characterized by large rivers (Fig. 1). Particularly UZJ is a region with numerous rivers and diverse limestone landscapes (karst) (Fig. 2). The mainstream of UZJ are Nanpanjiang River and Hongshuihe River (Fig. 2). UZJ also includes the upper reaches of the tributaries Youjiang and Zuojiang rivers (Fig. 2). These two rivers are very close to the mainstreams, with a nearest distance of ~20 km and ~10 km to Nanpanjiang and Hongshuihe rivers, respectively (Fig. 2), and their topography and habitats are quite the same to the mainstream (Ying et al., 1993Ying, T. S, Zhang, Y. L. & Boufford, D. E. 1993. The endemic genera of seed plants in China. Science Press, Beijing.; Fang et al., 1995Fang, R.-Z., Bai, P.-Y., Huang G.-B. & Wei Y.-G. 1995. 滇黔桂热带亚热带 (滇黔桂地区和北部湾地区) 种子植物区系 [A floristic study on the seed plants from tropics and subtropics of Dian-Qian-Gui]. Acta Botanica Yunnanica S7: 111–150 [in Chinese].; Hou et al., 2010Hou, M.-F., López-Pujol, J., Qin, H.-N, Wang, L.-S. & Liu, Y. 2010. Distribution pattern and conservation priorities for vascular plants in Southern China: Guangxi Province as a case study. Botanical Studies 51: 377–386.).

Determination of diversity and endemism centres

The numbers of total species and endemic species were counted for each geographic region. To detect the diversity centre (distribution centre of species richness), area- and habitat-adjusted species density (SD) was calculated using the formula SD = NT/[ln(A) + ln(E)], where NT is the species richness (the number of total species of the region), A is the area of the region (km2), and E is the habitat heterogeneity estimated by the elevation range (the difference between the highest and the lowest elevation in the region) according to Tang et al. (2006Tang, Z., Wang, Z., Zheng, C. & Fang, J. 2006. Biodiversity in China’s mountains. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment 4: 347–352. http://dx.doi.org/10.1890/1540-9295(2006)004[0347:bicm]2.0.co;2). The data of area and habitat heterogeneity for each geographic region are log-transferred to minimize their impacts on the calculation of species density using a revised method described in Qian (1998Qian, H. 1998. Large-scale biogeographic patterns of vascular plant richness in North America: an analysis at the genera level. Journal of Biogeography 25: 829–836. http://dx.doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2699.1998.00247.x) and Tang et al. (2006Tang, Z., Wang, Z., Zheng, C. & Fang, J. 2006. Biodiversity in China’s mountains. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment 4: 347–352. http://dx.doi.org/10.1890/1540-9295(2006)004[0347:bicm]2.0.co;2).

To determine the endemism centre(s), area- and habitat-adjusted endemism index (EI) was calculated using the formula EI = [NE/(NT − NE)]/[ln(A) + ln(E)], where NT is the number of total species, NE is the number of endemic species, A is the area of the region (km2), and E is the habitat heterogeneity.

To explore the correlation of species diversity and main geographic factors, the Pearson correlation coefficient between species diversity (i.e. number of total species, number of endemic species, endemic index) and three factors [region area, distance to the equator, and habitat heterogeneity (elevation range)] was calculated using SPSS software v17.0.

RESULTSTop

Based on the comprehensive surveys on all the described species, twenty-nine species of Hiptage were identified in this study (see Appendix). Two regions, Indo-China Peninsula and UZJ, were identified as the main diversity centres because they have the highest values of species density, both ≥0.65 (Table 1 and Appendix). There were 16 species in Indo-China Peninsula, in which 10 were endemic, mostly in Thailand at the south of the peninsula. In UZJ, six out the total seven Hiptage species were endemic (Table 1). These two regions were also recognized as endemism centres because both regions had an endemism index >0.1 (Fig. 4 and Table 1). UZJ was especially distinctive for its highest endemism, with a value of endemism index about five times of the second, Indo-China Peninsula (Fig. 4 and Table 1). This result made UZJ the distribution centre of endemic species of Hiptage. All the Hiptage species in UZJ have obviously reduced glands, with only two, one or no sepal gland (Appendix). Such floral trait is found to be a derived character in the family according to a complete generic phylogeny with both morphological and molecular data (Davis & Anderson, 2010Davis, C. C. & Anderson, W. R. 2010. A complete generic phylogeny of Malpighiaceae inferred from nucleotide sequence data and morphology. American Journal of Botany 97: 2031–2048. http://dx.doi.org/10.3732/ajb.1000146).

The endemic species in UZJ were mostly distributed along the rivers and valleys (Fig. 2), with some species occurred at the nearby limestone hills. Three rare endemic species with only one recorded place, i.e. Hiptage luodianensis S. K. Chen, H. fraxinifolia F. N. Wei, and H. multiflora F. N. Wei were found in the valley of Hongshuihe, Zuojiang, and Yongjiang rivers, respectively (Fig. 2). The other three species with two or more recorded places, i.e. H. lanceolata Arènes, H. tianyangensis F. N. Wei, and H. minor Dunn were also distributed along the Hongshuihe and Youjiang valleys (Fig. 2).

Statistical analysis revealed that the distributions of species diversity, measured by total number of total species (species richness), number of endemic species and endemism index, were not correlated with the region area, the distance to the equator, or the elevation range (Table 2).

DISCUSSIONTop

This study pointed out upper reaches of Zhujiang River in South China is not only the northern distribution edge of the tropical genus Hiptage but also its diversity and endemism centre. The correlation analyses found no associations of species diversity and endemism with geographic factors including region size, distance to the equator, and habitat heterogeneity (elevation range) (Tables 1 and 2). These facts suggest the formation of this diversity and endemism centre of Hiptage cannot be explained by large-scaled geographic factors and mainly is resulted from recent evolution caused by local topographic features or intrinsic traits of the genus, which I discuss in detail below.

| Table 2. Correlation between species richness, species density, endemism index, and three geographic factors. |

|

|

Geographic factors

|

|

Distance to the equator

|

ln(area)

|

ln(elevation range)

|

|

Species richness

|

r = −0.6521,

P = 0.594

|

r = 0.5402,

P = 0.427

|

r = 0.2004,

P = 0.525

|

|

Species density

|

r = −0.5683,

P = 0.970

|

r = 0.4446,

P = 0.723

|

r = 0.1531,

P = 0.625

|

|

Endemism index

|

r = 0.5500,

P = 0.341

|

r = −0.6232,

P = 0.333

|

r = −0.1576,

P = 0.735

|

|

Rivers and monsoon climate

Not only UZJ but also Indo-China peninsula (another centre of species diversity and endemism of Hiptage) are characterized by large rivers (Fig. 1). In Indo-China Peninsula, all the rivers such as Mekong River and Salween River are of north–south direction (Fig. 1). This flow direction can promote the northward spread of Hiptage since this tropical genus can only find suitable habitat along the riverside where is far away from typical tropical climate (Anderson et al., 2006Anderson, W. R., Anderson, C. & Davis, C. C. 2006–. Malpighiaceae. University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. Retrieved September 10, 2014 from http://herbarium.lsa.umich.edu/malpigh/index.html–; Ren et al., 2013Ren, M.-X., Zhong, Y.-F. & Song, X.-Q. 2013. Mirror-image flowers without buzz pollination in the Asia-endemic Hiptage benghalensis (Malpighiaceae). Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society 173: 764 –774. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/boj.12101). The long-distance dispersal of Hiptage is mainly achieved via its three-winged fruits, which can help the fruits to disperse over oceans (Davis et al., 2002Davis, C. C., Bell, C. D., Mathews, S. & Donoghue, M. J. 2002. Laurasian migration explains Gondwanan disjunctions: evidence from Malpighiaceae. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 99: 6833–6837. http://dx.doi.org/10.1073/pnas.102175899). UZJ is the most important diversity and endemism centre of Hiptage (Figs. 2 and 4, and Table 1) and contains numerous mountains and rivers with north-west–south-east direction (Figs. 1 and 2). These rivers are smaller than Mekong, Salween, and Red rivers but their valleys and slopes are also the home to many narrowly-endemic Hiptage species (Ren et al., 2013Ren, M.-X., Zhong, Y.-F. & Song, X.-Q. 2013. Mirror-image flowers without buzz pollination in the Asia-endemic Hiptage benghalensis (Malpighiaceae). Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society 173: 764 –774. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/boj.12101; Fig. 2).

More importantly, both UZJ and Indo-China Peninsula are close to the Tibetan Plateau and Himalaya (Fig. 1). The Himalayan uplift created tropical monsoon climate in its southern and eastern regions and the role of monsoon climate for species spread and speciation were already widely acknowledged in the nearby Hengduan Mountains (Fig. 1; Chapman & Wang 2002Chapman, G. P. & Wang, Y. Z. 2002. The plant life of China. Diversity and distribution. Springer-Verlag, Berlin & Heidelberg. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/978-3-662-04838-2; López-Pujol et al., 2006López-Pujol, J., Zhang, F.-M & Ge, S. 2006. Plant biodiversity in China: richly varied, endangered, and in need of conservation. Biodiversity and Conservation 15: 3983–4026. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10531-005-3015-2). Monsoon climate in Indo-China Peninsula and nearby regions is characterized by strong northward wind in the summer (approximately from April to October), which is also rain season (Wu & Zhang, 1998Wu, G. & Zhang, Y. 1998. Tibetan plateau forcing and the timing of the monsoon onset over South Asia and the South China Sea. Monthly Weather Review 126: 913–927. http://dx.doi.org/10.1175/1520-0493(1998)126<0913:tpfatt>2.0.co;2). In UZJ, the mainstream Hongshuihe River and two main branches (Youjiang and Zuojiang rivers) are all north-west–south-east direction (Fig. 2). This flow direction can bring the monsoon climate northward and promote the spread of Hiptage along the river valleys and even to the north bank of Hongshuihe River (Fig. 2). This is why all the Hiptage species in UZJ are distributed along the rivers and, when the river (Hongshuihe and Nanpanjiang sections) changes the flow to west–east direction, no Hiptage species move northward anymore (Fig. 2).

However, a question remains: why the Red River and the upper reaches of Mekong and Salween rivers (Figs. 1 and 2) have not formed a diversity or endemism centre of the genus Hiptage, given that their north–south flow direction also have the potential for species spread? The main reason probably is that the valleys of Mekong and Salween rivers are so wide that the three-winged fruits of Hiptage can disperse over a very long distance along the valleys, resulting in strong and continuous gene flow between the lower and upper reaches. Most mountains in this region are also of north–south direction and in good connectivity, which further maintains gene flow connecting upper and middle or lower reaches of rivers. This is why the only one endemic species on the Salween River, H. yunnanensis Huang ex S. K. Chen, occurs in the extraordinarily complex Hengduan Mountains in the northwestern Yunnan Province (Fig. 1) far away from the middle and lower reaches of the river. The valley of Red River is by far much wider and shorter than Mekong and Salween rivers, and gene flow along the Red River is strong enough to maintain species connectivity. Therefore it is not surprising that there is no endemic species along Red River, even it is only ~60 km away from UZJ (Fig. 2).

Highly-fragmented limestone landscapes

Another reason for UZJ as a diversification centre is its vast fragmentary limestone landscapes. Southwestern China has the largest continuous limestone areas in the world (Clements et al., 2006Clements, R., Sodhi, N. S., Schilthuizen, M. & Ng P. K. L. 2006. Limestone karsts of Southeast Asia: Imperiled arks of biodiversity. Bioscience 56: 733–742. http://dx.doi.org/10.1641/0006-3568(2006)56[733:lkosai]2.0.co;2; Hou et al., 2010Hou, M.-F., López-Pujol, J., Qin, H.-N, Wang, L.-S. & Liu, Y. 2010. Distribution pattern and conservation priorities for vascular plants in Southern China: Guangxi Province as a case study. Botanical Studies 51: 377–386.), which includes the UZJ and the biodiversity hotspot at borders of Guizhou–Yunnan–Guangxi provinces (Hou et al., 2010Hou, M.-F., López-Pujol, J., Qin, H.-N, Wang, L.-S. & Liu, Y. 2010. Distribution pattern and conservation priorities for vascular plants in Southern China: Guangxi Province as a case study. Botanical Studies 51: 377–386.). The limestone area here experienced severe erosion due to heavy rainfalls (Zhu et al., 2003Zhu, H., Wang, H., Li, B. & Sirirugsa, P. 2003. Biogeography and floristic affinities of the limestone flora in southern Yunnan, China. Annals of Missouri Botanical Garden 90: 444–465. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/3298536; Hou et al., 2010Hou, M.-F., López-Pujol, J., Qin, H.-N, Wang, L.-S. & Liu, Y. 2010. Distribution pattern and conservation priorities for vascular plants in Southern China: Guangxi Province as a case study. Botanical Studies 51: 377–386.) and is distinctive for its fengcong and fenglin, i.e. partially or completed isolated karst peaks (Fig. 2). These separate peaks, together with numerous slopes and pits with different orientations, may provide isolated microhabitats for plants (Fang et al., 1995Fang, R.-Z., Bai, P.-Y., Huang G.-B. & Wei Y.-G. 1995. 滇黔桂热带亚热带 (滇黔桂地区和北部湾地区) 种子植物区系 [A floristic study on the seed plants from tropics and subtropics of Dian-Qian-Gui]. Acta Botanica Yunnanica S7: 111–150 [in Chinese].; Zhu et al., 2003Zhu, H., Wang, H., Li, B. & Sirirugsa, P. 2003. Biogeography and floristic affinities of the limestone flora in southern Yunnan, China. Annals of Missouri Botanical Garden 90: 444–465. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/3298536; Clements et al., 2006Clements, R., Sodhi, N. S., Schilthuizen, M. & Ng P. K. L. 2006. Limestone karsts of Southeast Asia: Imperiled arks of biodiversity. Bioscience 56: 733–742. http://dx.doi.org/10.1641/0006-3568(2006)56[733:lkosai]2.0.co;2; Hou et al., 2010Hou, M.-F., López-Pujol, J., Qin, H.-N, Wang, L.-S. & Liu, Y. 2010. Distribution pattern and conservation priorities for vascular plants in Southern China: Guangxi Province as a case study. Botanical Studies 51: 377–386.). Clements et al. (2006Clements, R., Sodhi, N. S., Schilthuizen, M. & Ng P. K. L. 2006. Limestone karsts of Southeast Asia: Imperiled arks of biodiversity. Bioscience 56: 733–742. http://dx.doi.org/10.1641/0006-3568(2006)56[733:lkosai]2.0.co;2) attributed the high level of species richness and endemism in Southeast Asian karsts, including Southwestern China, to their high diversity of microhabitats and climatic conditions. This is particularly the case in UZJ and surrounding areas since the limestone landscapes here are highly fragmented and remained relatively stable during the last glacial period of the Pleistocene (Li, 1994Li, X.-W. 1994. 中国特有种子植物属在云南的两大生物多样性中心及其特征 [Two big biodiversity centres of Chinese endemic genera of seed plants and their characteristics in Yunnan Province]. Acta Botanica Yunnanica 16: 221–227 [in Chinese].; Hou et al., 2010Hou, M.-F., López-Pujol, J., Qin, H.-N, Wang, L.-S. & Liu, Y. 2010. Distribution pattern and conservation priorities for vascular plants in Southern China: Guangxi Province as a case study. Botanical Studies 51: 377–386.), making this region not only a survival center for relict species, but also an important place for species diversification (Chapman & Wang, 2002Chapman, G. P. & Wang, Y. Z. 2002. The plant life of China. Diversity and distribution. Springer-Verlag, Berlin & Heidelberg. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/978-3-662-04838-2; Qian, 2002Qian, H. 2002. A comparison of the taxonomic richness of temperate plants in East Asia and North America. American Journal of Botany 89: 1818–1825. http://dx.doi.org/10.3732/ajb.89.11.1818; López-Pujol et al., 2011López-Pujol, J., Zhang, F.-M, Sun, H.-Q., Ying, T.-S. & Ge, S. 2011. Centres of plant endemism in China: places for survival or for speciation? Journal of Biogeography 38: 1267–1280. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2699.2011.02504.x).

For Hiptage, many endemic species are found exclusively on limestone rocks in UZJ and Indo-China Peninsula (Sirirugsa, 1991Sirirugsa, P. 1991. Malpighiaceae. In: Smitinand, T. & Larsen, K. (Eds.), Flora of Thailand 5(3). The Forest Herbarium, Royal Forest Department, Bangkok: 272–299.). In UZJ, some species such as H. tianyangensis and H. multiflora occupy the tops or sunny slopes of hills, some species including H. minor, H. lanceolata and H. luodianensis can only grow at the bottom of river valleys, while other species such as H. fraxinifolia and H. benghalensis are found predominantly in dense forests or shrubs (Chen & Funston, 2008Chen, S. & Funston, A. M. 2008. Malpighiaceae. In: Wu, Z. Y., Raven, P. H. & Hong, D. Y. (Eds.), Flora of China 11 (Oxalidaceae through Aceraceae). Science Press, Beijing & Missouri Botanical Garden Press, St. Louis: 132–138.; M. X. Ren, pers. obs.). These local separations of species distributions suggest that habitat differentiation is quite possible between species.

UZJ is also the distribution and endemism centre for other tropical families including Gesneriaceae and Begoniaceae (Li & Wang, 2004Li, Z. Y. & Wang, Y. Z. 2004. 中国苦苣苔科植物 [Gesneriaceae of China]. Henan Scientific and Technical Publishing House, Zhengzhou [in Chinese].; Wei et al., 2004Wei, Y.-G., Zhong, S.-H. & Wen, H.-Q. 2004. 广西苦苣苔科植物区系和生态特点研究 [Studies on the flora and ecology Gesneriaceae in Guangxi Province]. Acta Botanica Yunnanica 26: 173–182 [in Chinese].; Hou et al., 2010Hou, M.-F., López-Pujol, J., Qin, H.-N, Wang, L.-S. & Liu, Y. 2010. Distribution pattern and conservation priorities for vascular plants in Southern China: Guangxi Province as a case study. Botanical Studies 51: 377–386.). For example, many recently-evolved genus and species of Gesneriaceae such as Allocheilos W. T. Wang, Thamnocharis W. T. Wang, Tengia Chun, and Lagarosolen W. T. Wang are only found in UZJ and its neighboring areas (Lu et al., 1989Lu, Y. X., Huang, G. B. & Liang, C. F. 1989. 广西特有植物研究 [Study on the endemic plants from Guangxi]. Guihaia 9: 37–58 [in Chinese].; Wei et al., 2004Wei, Y.-G., Zhong, S.-H. & Wen, H.-Q. 2004. 广西苦苣苔科植物区系和生态特点研究 [Studies on the flora and ecology Gesneriaceae in Guangxi Province]. Acta Botanica Yunnanica 26: 173–182 [in Chinese].). In Guangxi Province, Wei et al. (2004Wei, Y.-G., Zhong, S.-H. & Wen, H.-Q. 2004. 广西苦苣苔科植物区系和生态特点研究 [Studies on the flora and ecology Gesneriaceae in Guangxi Province]. Acta Botanica Yunnanica 26: 173–182 [in Chinese].) found 16 out 38 genus of Gesneriaceae that were distributed exclusively in karst regions, while Lu et al. (1995Lu, Y. X., Huang, G. B. & Liang, C. F. 1989. 广西特有植物研究 [Study on the endemic plants from Guangxi]. Guihaia 9: 37–58 [in Chinese].) and Hou et al. (2010Hou, M.-F., López-Pujol, J., Qin, H.-N, Wang, L.-S. & Liu, Y. 2010. Distribution pattern and conservation priorities for vascular plants in Southern China: Guangxi Province as a case study. Botanical Studies 51: 377–386.) even reported ~80% of the endemic genera are only distributed in limestone areas. Furthermore, most endemic species of Gesneriaceae are restricted to the highly-fragmented limestone areas between Youjiang and Zuojiang rivers (Fig. 2; Wei et al., 2004Wei, Y.-G., Zhong, S.-H. & Wen, H.-Q. 2004. 广西苦苣苔科植物区系和生态特点研究 [Studies on the flora and ecology Gesneriaceae in Guangxi Province]. Acta Botanica Yunnanica 26: 173–182 [in Chinese].). These facts further suggest the evolutionary diversification of these tropical taxa in UZJ mainly resulted from fragmented limestone landscapes (Li, 1994Li, X.-W. 1994. 中国特有种子植物属在云南的两大生物多样性中心及其特征 [Two big biodiversity centres of Chinese endemic genera of seed plants and their characteristics in Yunnan Province]. Acta Botanica Yunnanica 16: 221–227 [in Chinese].; Fang et al., 1995Fang, R.-Z., Bai, P.-Y., Huang G.-B. & Wei Y.-G. 1995. 滇黔桂热带亚热带 (滇黔桂地区和北部湾地区) 种子植物区系 [A floristic study on the seed plants from tropics and subtropics of Dian-Qian-Gui]. Acta Botanica Yunnanica S7: 111–150 [in Chinese].; Wei et al., 2004Wei, Y.-G., Zhong, S.-H. & Wen, H.-Q. 2004. 广西苦苣苔科植物区系和生态特点研究 [Studies on the flora and ecology Gesneriaceae in Guangxi Province]. Acta Botanica Yunnanica 26: 173–182 [in Chinese].).

Highly-specialized pollination mechanism

Hiptage is characterized with mirror-image flowers with heteromorphic stamens and longitudinal anthers (Fig. 3A; Ren et al., 2013Ren, M.-X., Zhong, Y.-F. & Song, X.-Q. 2013. Mirror-image flowers without buzz pollination in the Asia-endemic Hiptage benghalensis (Malpighiaceae). Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society 173: 764 –774. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/boj.12101). Mirror-image flowers are a sexual polymorphism in which the style deflects away from the floral axis either to the left (left-styled flower) or the right (right-styled flower) (Jesson & Barrett, 2002Jesson, L. K. & Barrett, S. C. H. 2002. Enantiostyly: solving the puzzle of mirror-image flowers. Nature 417: 707. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/417707a; Gao et al., 2006Gao, J.-Y., Ren, P.-Y., Yang, Z.-H. & Li, Q.-J. 2006. The pollination ecology of Paraboea rufescens (Gesneriaceae), a buzz-pollinated tropical herb with mirror-image flowers. Annals of Botany 97: 371–376. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/aob/mcj044; Ren et al., 2013Ren, M.-X., Zhong, Y.-F. & Song, X.-Q. 2013. Mirror-image flowers without buzz pollination in the Asia-endemic Hiptage benghalensis (Malpighiaceae). Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society 173: 764 –774. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/boj.12101). Normally the pollinators for mirror-image flowers are large-bodied pollen-collecting honeybees such as Apis dorsata (Fig. 3B; Ren et al., 2013Ren, M.-X., Zhong, Y.-F. & Song, X.-Q. 2013. Mirror-image flowers without buzz pollination in the Asia-endemic Hiptage benghalensis (Malpighiaceae). Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society 173: 764 –774. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/boj.12101). This highly-specialized insect-pollination mechanism can facilitate cross-pollinations between left- and right-styled flowers through two deflected sexual organs touching left and right sides of the pollinator’s abdomen respectively (Jesson & Barrett, 2002Jesson, L. K. & Barrett, S. C. H. 2002. Enantiostyly: solving the puzzle of mirror-image flowers. Nature 417: 707. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/417707a; Ren et al., 2013Ren, M.-X., Zhong, Y.-F. & Song, X.-Q. 2013. Mirror-image flowers without buzz pollination in the Asia-endemic Hiptage benghalensis (Malpighiaceae). Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society 173: 764 –774. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/boj.12101). Therefore, the spatial separation of the deflected stigma and anther (herkogamy; Webb & Lloyd, 1986Webb, C. J. & Lloyd, D. G. 1986. The avoidance of interference between the presentation of pollen and stigmas in angiosperms II. Herkogamy. New Zealand Journal of Botany 24: 163–178. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/0028825X.1986.10409726; Ren & Zhang, 2004Ren, M. X., Zhang, D. Y. 2004. Herkogamy. In: Zhang, D. Y. (Ed.), 植物生活史进化与繁殖生态学 [Plant life-history evolution and reproductive ecology]. Science Press, Beijing: 302–321 [in Chinese].) must be under selection to adapt to the pollinator’s body size to ensure successful pollen transfers between two floral types (Jesson & Barrett, 2002Jesson, L. K. & Barrett, S. C. H. 2002. Enantiostyly: solving the puzzle of mirror-image flowers. Nature 417: 707. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/417707a; Gao et al., 2006Gao, J.-Y., Ren, P.-Y., Yang, Z.-H. & Li, Q.-J. 2006. The pollination ecology of Paraboea rufescens (Gesneriaceae), a buzz-pollinated tropical herb with mirror-image flowers. Annals of Botany 97: 371–376. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/aob/mcj044; Ren et al., 2013Ren, M.-X., Zhong, Y.-F. & Song, X.-Q. 2013. Mirror-image flowers without buzz pollination in the Asia-endemic Hiptage benghalensis (Malpighiaceae). Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society 173: 764 –774. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/boj.12101).

Due to its accurate pollen transfers and high pollination efficiency, mirror-image flowers have the potential to generate floral isolation and facilitate speciation (Grant, 1994Grant, V. 1994. Modes and origins of mechanical and ethological isolation in angiosperm. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 91: 3–10. http://dx.doi.org/10.1073/pnas.91.1.3; Armbruster & Muchhala, 2009Armbruster, S. W. & Muchhala, N. 2009. Associations between floral specialization and species diversity: cause, effect, or correlation? Evolutionary Ecology 23: 159–179. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10682-008-9259-z). Hiptage species differ significantly in flower size and length of sexual organs (Chen & Funston, 2008Chen, S. & Funston, A. M. 2008. Malpighiaceae. In: Wu, Z. Y., Raven, P. H. & Hong, D. Y. (Eds.), Flora of China 11 (Oxalidaceae through Aceraceae). Science Press, Beijing & Missouri Botanical Garden Press, St. Louis: 132–138.), and it is likely that herkogamy also varies greatly among species. Such differences probably reflect adaptations to different pollinators or different parts of the same pollinator, a phenomenon found in other herkogamous species (Medrano et al., 2005Medrano, M., Herrera, C. M. & Barrett, S. C. H. 2005. Herkogamy and mating patterns in the self-compatible daffodil Narcissus longispathus. Annals of Botany 95: 1105–1111. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/aob/mci129; Kay & Sargent, 2009Kay, K. M. & Sargent, R. D. 2009. The role of animal pollination in plant speciation: Integrating ecology, geography, and genetics. Annual Reviews of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics 40: 637–656. http://dx.doi.org/10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.110308.120310) or species with similar specialized floral traits (Armbruster & Muchhala, 2009Armbruster, S. W. & Muchhala, N. 2009. Associations between floral specialization and species diversity: cause, effect, or correlation? Evolutionary Ecology 23: 159–179. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10682-008-9259-z).

Other tropical families with their diversification centre at UZJ also show specialized floral syndromes and pollination mechanisms. For example, Gesneriaceae are well-known for its highly-specialized floral traits and pollination mechanism (Lu et al., 1989Lu, Y. X., Huang, G. B. & Liang, C. F. 1989. 广西特有植物研究 [Study on the endemic plants from Guangxi]. Guihaia 9: 37–58 [in Chinese].; Fang et al., 1995Fang, R.-Z., Bai, P.-Y., Huang G.-B. & Wei Y.-G. 1995. 滇黔桂热带亚热带 (滇黔桂地区和北部湾地区) 种子植物区系 [A floristic study on the seed plants from tropics and subtropics of Dian-Qian-Gui]. Acta Botanica Yunnanica S7: 111–150 [in Chinese].; Li & Wang, 2004Li, Z. Y. & Wang, Y. Z. 2004. 中国苦苣苔科植物 [Gesneriaceae of China]. Henan Scientific and Technical Publishing House, Zhengzhou [in Chinese].) and also contain species with mirror-image flowers in this region (Gao et al., 2006Gao, J.-Y., Ren, P.-Y., Yang, Z.-H. & Li, Q.-J. 2006. The pollination ecology of Paraboea rufescens (Gesneriaceae), a buzz-pollinated tropical herb with mirror-image flowers. Annals of Botany 97: 371–376. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/aob/mcj044). Begoniaceae are also distinctive for its unisexual flowers and this trait is probably an adaptation to stressful habitats on limestones (Hou et al., 2010Hou, M.-F., López-Pujol, J., Qin, H.-N, Wang, L.-S. & Liu, Y. 2010. Distribution pattern and conservation priorities for vascular plants in Southern China: Guangxi Province as a case study. Botanical Studies 51: 377–386.). Species of both families in UZJ region are mostly neoendemics (Lu et al., 1989Lu, Y. X., Huang, G. B. & Liang, C. F. 1989. 广西特有植物研究 [Study on the endemic plants from Guangxi]. Guihaia 9: 37–58 [in Chinese].; Fang et al., 1995Fang, R.-Z., Bai, P.-Y., Huang G.-B. & Wei Y.-G. 1995. 滇黔桂热带亚热带 (滇黔桂地区和北部湾地区) 种子植物区系 [A floristic study on the seed plants from tropics and subtropics of Dian-Qian-Gui]. Acta Botanica Yunnanica S7: 111–150 [in Chinese].; Li & Wang 2004Li, Z. Y. & Wang, Y. Z. 2004. 中国苦苣苔科植物 [Gesneriaceae of China]. Henan Scientific and Technical Publishing House, Zhengzhou [in Chinese].; Hou et al., 2010Hou, M.-F., López-Pujol, J., Qin, H.-N, Wang, L.-S. & Liu, Y. 2010. Distribution pattern and conservation priorities for vascular plants in Southern China: Guangxi Province as a case study. Botanical Studies 51: 377–386.). Nevertheless, this hypothesis about the association of species diversity and floral specialization in UZJ is in need of further experimental tests.

In conclusion, upper reaches of Zhujiang River can be seen as the “evolutionary front” of tropical plants in China due to its predominant proportion of narrowly-endemic and recently-evolved species of Hiptage (Malpighiaceae) and other tropical groups such as Gesneriaceae and Begoniaceae. Environmental factors (rivers with monsoon climate and limestone landscapes) and intrinsic traits of the plants such as highly-specialized pollination systems are responsible for the origin and evolution of the biodiversity in this “evolutionary front”, with the environmental factors more likely being the most significant driving factors. Tropical plants are the main composition of UZJ and its neighbouring regions and should be paid enough attention in the studies of the origin and evolution of this unusual biodiversity hotspot, which is one of globally-important biodiversity hotspots.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTSTop

I thank Dr. X.-Q. Song in Hainan University for his discussion on an early idea of this manuscript. Financial supports are provided by National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant number: 31170356) and a start-up fund from Hainan University (kyqd1501).

APPENDIXTop

| Appendix. Geographic distribution and main floral traits of the Hiptage species. |

|

Species

|

Main floral feature

|

Distribution

|

References

|

|

Hiptage benghalensis (L.) Kurz

|

Flowers fragrant. Sepal gland 1, ~4–5 × 2 mm, thick, oblong, 1/2 decurrent to pedicel. Stamens differing in size, longest 8–12 mm, others 3–5 mm.

|

South Asia (India, Pakistan, Bengal, Sri Lanka)

Islands (Indonesia, Philippines, Andaman)

Indo-China Peninsula (Myanmar, Laos, Cambodia, Thailand, Vietnam, Malaysia)

Yunnan Province

Upper reaches of Zhujiang River

|

Srivastava, 1992Srivastava, R. C. 1992. Taxonomic revision of the genus Hiptage Gaerlner (Malpighiaceae) in India. Candollea 47: 601–612.;

Chen & Funston, 2008Chen, S. & Funston, A. M. 2008. Malpighiaceae. In: Wu, Z. Y., Raven, P. H. & Hong, D. Y. (Eds.), Flora of China 11 (Oxalidaceae through Aceraceae). Science Press, Beijing & Missouri Botanical Garden Press, St. Louis: 132–138.; Ren et al., 2013Ren, M.-X., Zhong, Y.-F. & Song, X.-Q. 2013. Mirror-image flowers without buzz pollination in the Asia-endemic Hiptage benghalensis (Malpighiaceae). Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society 173: 764 –774. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/boj.12101

|

|

H. candicans Hook. f.

|

Sepal gland 1, base decurrent to pedicel

|

South Asia (India)

Islands (Indonesia)

Indo-China Peninsula (Myanmar, Laos, Thailand)

Yunnan Province

|

Chen & Funston, 2008Chen, S. & Funston, A. M. 2008. Malpighiaceae. In: Wu, Z. Y., Raven, P. H. & Hong, D. Y. (Eds.), Flora of China 11 (Oxalidaceae through Aceraceae). Science Press, Beijing & Missouri Botanical Garden Press, St. Louis: 132–138.

|

|

H. acuminata Wall. ex A. Juss.

|

Sepal gland 1, small, 1/4 decurrent to pedicel

|

South Asia (India, Bengal )

Indo-China Peninsula (Myanmar)

Yunnan Province

|

Chen & Funston, 2008Chen, S. & Funston, A. M. 2008. Malpighiaceae. In: Wu, Z. Y., Raven, P. H. & Hong, D. Y. (Eds.), Flora of China 11 (Oxalidaceae through Aceraceae). Science Press, Beijing & Missouri Botanical Garden Press, St. Louis: 132–138.

|

|

H. parvifolia Wight & Arn.

|

Sepal gland 5, ovoid,

~3 mm long

|

South Asia (India, Sri Lanka)

Indo-China Peninsula (Myanmar)

Islands (Philippines, Indonesia)

|

Niedenzu 1928Niedenzu, F. 1928. Malpighiaceae. In: Engler, A. (Ed.), Das Pflanzenreich IV. 141. Verlag von Wilhelm Engelmann, Leipzig: 1–870.; Srivastava, 1992Srivastava, R. C. 1992. Taxonomic revision of the genus Hiptage Gaerlner (Malpighiaceae) in India. Candollea 47: 601–612.

|

|

H. obtusifolia DC.

|

Sepal gland 5,

~2 × 0.75 mm

|

South Asia (India, Bengal)

Islands (Andaman, Indonesia, Philippines)

Indo-China Peninsula (Thailand)

|

Srivastava, 1992Srivastava, R. C. 1992. Taxonomic revision of the genus Hiptage Gaerlner (Malpighiaceae) in India. Candollea 47: 601–612.

|

|

H. sericea Hook. f.

|

Sepal gland 5, oblong 2–3 mm long, 1/4 decurrent to pedicel

|

South Asia (India)

Indo-China Peninsula (Myanmar, Malaysia, Thailand)

|

Srivastava, 1992Srivastava, R. C. 1992. Taxonomic revision of the genus Hiptage Gaerlner (Malpighiaceae) in India. Candollea 47: 601–612.

|

H. jacobsii

R. C. Srivast.

|

Sepal gland 5,

~2 × 1 mm

|

South Asia (India endemic)

|

Srivastava, 1992Srivastava, R. C. 1992. Taxonomic revision of the genus Hiptage Gaerlner (Malpighiaceae) in India. Candollea 47: 601–612.

|

|

H nayarii R. C. Srivast.

|

Sepal gland 5, round 2–3 mm long

|

South Asia (India endemic)

|

Srivastava, 1992Srivastava, R. C. 1992. Taxonomic revision of the genus Hiptage Gaerlner (Malpighiaceae) in India. Candollea 47: 601–612.

|

|

H. thothathrii N. P. Balakr. & R. C. Srivast.

|

Sepal gland 5, oblong

~4 ×1 mm

|

Islands (Andaman endemic)

|

Srivastava, 1992Srivastava, R. C. 1992. Taxonomic revision of the genus Hiptage Gaerlner (Malpighiaceae) in India. Candollea 47: 601–612.

|

|

H. luzonica Merr.

|

Sepal gland 1, orbicular

|

Islands (Philippines endemic)

|

Jacobs, 1955Jacobs, M. 1955. Malpighiaceae. In: Steenis, C. G. G. J. van (Ed.), Flora Malesiana Ser. 1, 5(2). Noordhoff-Kolff, Djakarta: 125–145.

|

|

H. pubescens Merr.

|

Sepal gland 1, orbicular, cup shaped with thicken rims, ~1 mm

|

Islands (Philippines endemic)

|

Jacobs, 1955Jacobs, M. 1955. Malpighiaceae. In: Steenis, C. G. G. J. van (Ed.), Flora Malesiana Ser. 1, 5(2). Noordhoff-Kolff, Djakarta: 125–145.

|

H. myrtifolia

A. Gray

|

Sepal gland 1

|

Islands (Fiji endemic)

|

Jacobs, 1955Jacobs, M. 1955. Malpighiaceae. In: Steenis, C. G. G. J. van (Ed.), Flora Malesiana Ser. 1, 5(2). Noordhoff-Kolff, Djakarta: 125–145.

|

|

H. lucida Pierre

|

Sepal gland 5, very small

|

Indo-China Peninsula (Vietnam, Thailand)

|

Sirirugsa, 1991Sirirugsa, P. 1991. Malpighiaceae. In: Smitinand, T. & Larsen, K. (Eds.), Flora of Thailand 5(3). The Forest Herbarium, Royal Forest Department, Bangkok: 272–299.

|

|

H. triacantha Pierre

|

Sepal gland 1, oblong ~1.5–3 × 0.7–1 mm, sometimes decurrent to pedicel

|

Indo-China Peninsula (Thailand endemic)

|

Sirirugsa, 1991Sirirugsa, P. 1991. Malpighiaceae. In: Smitinand, T. & Larsen, K. (Eds.), Flora of Thailand 5(3). The Forest Herbarium, Royal Forest Department, Bangkok: 272–299.

|

|

H. bullata Craib

|

Sepal gland 5, orbicular,

<1 mm

|

Indo-China Peninsula (Thailand endemic)

|

Sirirugsa, 1991Sirirugsa, P. 1991. Malpighiaceae. In: Smitinand, T. & Larsen, K. (Eds.), Flora of Thailand 5(3). The Forest Herbarium, Royal Forest Department, Bangkok: 272–299.

|

|

H. glabrifolia Craib

|

No sepal gland

|

Indo-China Peninsula (Thailand endemic)

|

Sirirugsa, 1991Sirirugsa, P. 1991. Malpighiaceae. In: Smitinand, T. & Larsen, K. (Eds.), Flora of Thailand 5(3). The Forest Herbarium, Royal Forest Department, Bangkok: 272–299.

|

|

H. detergens Craib

|

Sepal gland 1, ovate, 1–5 mm long

|

Indo-China Peninsula (Thailand endemic)

|

Sirirugsa, 1991Sirirugsa, P. 1991. Malpighiaceae. In: Smitinand, T. & Larsen, K. (Eds.), Flora of Thailand 5(3). The Forest Herbarium, Royal Forest Department, Bangkok: 272–299.

|

|

H. calcicola Sirirugsa

|

No sepal gland

|

Indo-China Peninsula (Thailand endemic)

|

Sirirugsa, 1987Sirirugsa, P. 1987. Three new species of Hiptage (Malpighiaceae) in Thailand. Nordic Journal of Botany 7: 277–280. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1756-1051.1987.tb00944.x;

Sirirugsa, 1991Sirirugsa, P. 1991. Malpighiaceae. In: Smitinand, T. & Larsen, K. (Eds.), Flora of Thailand 5(3). The Forest Herbarium, Royal Forest Department, Bangkok: 272–299.

|

|

H. gracilis Sirirugsa

|

No sepal gland

|

Indo-China Peninsula (Thailand endemic)

|

Sirirugsa, 1987Sirirugsa, P. 1987. Three new species of Hiptage (Malpighiaceae) in Thailand. Nordic Journal of Botany 7: 277–280. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1756-1051.1987.tb00944.x;

Sirirugsa, 1991Sirirugsa, P. 1991. Malpighiaceae. In: Smitinand, T. & Larsen, K. (Eds.), Flora of Thailand 5(3). The Forest Herbarium, Royal Forest Department, Bangkok: 272–299.

|

|

H. condita Craib

|

No sepal gland

|

Indo-China Peninsula (Thailand endemic)

|

Sirirugsa, 1991Sirirugsa, P. 1991. Malpighiaceae. In: Smitinand, T. & Larsen, K. (Eds.), Flora of Thailand 5(3). The Forest Herbarium, Royal Forest Department, Bangkok: 272–299.

|

|

H. monopteryx Sirirugsa

|

No sepal gland

|

Indo-China Peninsula (Thailand endemic)

|

Sirirugsa, 1987Sirirugsa, P. 1987. Three new species of Hiptage (Malpighiaceae) in Thailand. Nordic Journal of Botany 7: 277–280. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1756-1051.1987.tb00944.x;

Sirirugsa, 1991Sirirugsa, P. 1991. Malpighiaceae. In: Smitinand, T. & Larsen, K. (Eds.), Flora of Thailand 5(3). The Forest Herbarium, Royal Forest Department, Bangkok: 272–299.

|

|

H. burkilliana Arènes

|

No sepal gland

|

Indo-China Peninsula (Malaysia)

|

Jacobs, 1955Jacobs, M. 1955. Malpighiaceae. In: Steenis, C. G. G. J. van (Ed.), Flora Malesiana Ser. 1, 5(2). Noordhoff-Kolff, Djakarta: 125–145.

|

|

H. yunnanensis Huang ex S. K. Chen

|

Sepal gland 1, small, 1/4–1/2 decurrent to pedicel

|

Yunnan Province (endemic to the upper reaches of Salween River)

|

Chen & Funston, 2008Chen, S. & Funston, A. M. 2008. Malpighiaceae. In: Wu, Z. Y., Raven, P. H. & Hong, D. Y. (Eds.), Flora of China 11 (Oxalidaceae through Aceraceae). Science Press, Beijing & Missouri Botanical Garden Press, St. Louis: 132–138.

|

|

H. fraxinifolia F. N. Wei

|

Sepal gland 1, not decurrent to pedicel

|

Upper reaches of Zhujiang River

|

Chen & Funston, 2008Chen, S. & Funston, A. M. 2008. Malpighiaceae. In: Wu, Z. Y., Raven, P. H. & Hong, D. Y. (Eds.), Flora of China 11 (Oxalidaceae through Aceraceae). Science Press, Beijing & Missouri Botanical Garden Press, St. Louis: 132–138.

|

|

H. tianyangensis F. N. Wei

|

Sepal gland 1, not decurrent to pedicel

|

Upper reaches of Zhujiang River

|

Chen & Funston, 2008Chen, S. & Funston, A. M. 2008. Malpighiaceae. In: Wu, Z. Y., Raven, P. H. & Hong, D. Y. (Eds.), Flora of China 11 (Oxalidaceae through Aceraceae). Science Press, Beijing & Missouri Botanical Garden Press, St. Louis: 132–138.

|

|

H. multiflora F. N. Wei

|

Sepal gland 1, not decurrent to pedicel

|

Upper reaches of Zhujiang River

|

Chen & Funston, 2008Chen, S. & Funston, A. M. 2008. Malpighiaceae. In: Wu, Z. Y., Raven, P. H. & Hong, D. Y. (Eds.), Flora of China 11 (Oxalidaceae through Aceraceae). Science Press, Beijing & Missouri Botanical Garden Press, St. Louis: 132–138.

|

|

H. lanceolata Arènes

|

No sepal gland

|

Upper reaches of Zhujiang River

|

Chen & Funston, 2008Chen, S. & Funston, A. M. 2008. Malpighiaceae. In: Wu, Z. Y., Raven, P. H. & Hong, D. Y. (Eds.), Flora of China 11 (Oxalidaceae through Aceraceae). Science Press, Beijing & Missouri Botanical Garden Press, St. Louis: 132–138.

|

|

H. minor Dunn

|

No sepal gland

|

Upper reaches of Zhujiang River

|

Chen & Funston, 2008Chen, S. & Funston, A. M. 2008. Malpighiaceae. In: Wu, Z. Y., Raven, P. H. & Hong, D. Y. (Eds.), Flora of China 11 (Oxalidaceae through Aceraceae). Science Press, Beijing & Missouri Botanical Garden Press, St. Louis: 132–138.

|

|

H. luodianensis S. K. Chen

|

Sepal gland 2

|

Upper reaches of Zhujiang River

|

Chen & Funston, 2008Chen, S. & Funston, A. M. 2008. Malpighiaceae. In: Wu, Z. Y., Raven, P. H. & Hong, D. Y. (Eds.), Flora of China 11 (Oxalidaceae through Aceraceae). Science Press, Beijing & Missouri Botanical Garden Press, St. Louis: 132–138.

|

|

REFERENCESTop

|

| 1. | Anderson, W. R. 1990. The origin of the Malpighiaceae—the evidence from morphology. Memoirs of the New York Botanical Garden 64: 210–224. |

|

| 2. |

Anderson, W. R., Anderson, C. & Davis, C. C. 2006–. Malpighiaceae. University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. Retrieved September 10, 2014 from http://herbarium.lsa.umich.edu/malpigh/index.html |

|

| 3. |

Armbruster, S. W. & Muchhala, N. 2009. Associations between floral specialization and species diversity: cause, effect, or correlation? Evolutionary Ecology 23: 159–179. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10682-008-9259-z |

|

| 4. |

Axelrod, D. I., Al-Shehbaz, I. & Raven, P. H. 1996. History of the modern flora of China. In: Zhang, A. & Wu, S. (Eds.), Floristic characteristics and diversity of East Asian plants. China Higher Education Press, Beijing: 43–55. |

|

| 5. |

Barrett, S. C. H., Jesson, L. K. & Baker, A. M. 2000. The evolution and function of stylar polymorphisms in flowering plants. Annals of Botany 85: 253–265. http://dx.doi.org/10.1006/anbo.1999.1067 |

|

| 6. |

Chapman, G. P. & Wang, Y. Z. 2002. The plant life of China. Diversity and distribution. Springer-Verlag, Berlin & Heidelberg. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/978-3-662-04838-2 |

|

| 7. |

Chen, C. H. 1993. Malpighiaceae. In: Huang, T. C. (Ed.), Flora of Taiwan 3 (2nd ed.). Lunwei Printing Company, Taipei: 565–566. |

|

| 8. |

Chen, S. & Funston, A. M. 2008. Malpighiaceae. In: Wu, Z. Y., Raven, P. H. & Hong, D. Y. (Eds.), Flora of China 11 (Oxalidaceae through Aceraceae). Science Press, Beijing & Missouri Botanical Garden Press, St. Louis: 132–138. |

|

| 9. |

Clements, R., Sodhi, N. S., Schilthuizen, M. & Ng P. K. L. 2006. Limestone karsts of Southeast Asia: Imperiled arks of biodiversity. Bioscience 56: 733–742. http://dx.doi.org/10.1641/0006-3568(2006)56[733:lkosai]2.0.co;2 |

|

| 10. |

Davis, C. C. & Anderson, W. R. 2010. A complete generic phylogeny of Malpighiaceae inferred from nucleotide sequence data and morphology. American Journal of Botany 97: 2031–2048. http://dx.doi.org/10.3732/ajb.1000146 |

|

| 11. |

Davis, C. C., Bell, C. D., Mathews, S. & Donoghue, M. J. 2002. Laurasian migration explains Gondwanan disjunctions: evidence from Malpighiaceae. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 99: 6833–6837. http://dx.doi.org/10.1073/pnas.102175899 |

|

| 12. |

Fang, R.-Z., Bai, P.-Y., Huang G.-B. & Wei Y.-G. 1995. 滇黔桂热带亚热带 (滇黔桂地区和北部湾地区) 种子植物区系 [A floristic study on the seed plants from tropics and subtropics of Dian-Qian-Gui]. Acta Botanica Yunnanica S7: 111–150 [in Chinese]. |

|

| 13. |

Gao, J.-Y., Ren, P.-Y., Yang, Z.-H. & Li, Q.-J. 2006. The pollination ecology of Paraboea rufescens (Gesneriaceae), a buzz-pollinated tropical herb with mirror-image flowers. Annals of Botany 97: 371–376. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/aob/mcj044 |

|

| 14. |

Grant, V. 1994. Modes and origins of mechanical and ethological isolation in angiosperm. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 91: 3–10. http://dx.doi.org/10.1073/pnas.91.1.3 |

|

| 15. |

Grierson, A. J. C. 1991. Malpighiaceae. In: Grierson, A. J. C. & Long, D. G. (Eds.), Flora of Bhutan 2(1). Royal Botanic Garden, Edinburgh: 40–42. |

|

| 16. |

Hou, M.-F., López-Pujol, J., Qin, H.-N, Wang, L.-S. & Liu, Y. 2010. Distribution pattern and conservation priorities for vascular plants in Southern China: Guangxi Province as a case study. Botanical Studies 51: 377–386. |

|

| 17. |

Jacobs, M. 1955. Malpighiaceae. In: Steenis, C. G. G. J. van (Ed.), Flora Malesiana Ser. 1, 5(2). Noordhoff-Kolff, Djakarta: 125–145. |

|

| 18. |

Jesson, L. K. & Barrett, S. C. H. 2002. Enantiostyly: solving the puzzle of mirror-image flowers. Nature 417: 707. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/417707a |

|

| 19. |

Kay, K. M. & Sargent, R. D. 2009. The role of animal pollination in plant speciation: Integrating ecology, geography, and genetics. Annual Reviews of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics 40: 637–656. http://dx.doi.org/10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.110308.120310 |

|

| 20. |

Li, X.-W. 1994. 中国特有种子植物属在云南的两大生物多样性中心及其特征 [Two big biodiversity centres of Chinese endemic genera of seed plants and their characteristics in Yunnan Province]. Acta Botanica Yunnanica 16: 221–227 [in Chinese]. |

|

| 21. |

Li, Z. Y. & Wang, Y. Z. 2004. 中国苦苣苔科植物 [Gesneriaceae of China]. Henan Scientific and Technical Publishing House, Zhengzhou [in Chinese]. |

|

| 22. |

Liu, J., Ouyang, Z., Pimm, S. L., Raven, P. H., Wang, X., Miao, H. & Han, N. 2003. Protecting China’s biodiversity. Science 300: 1240–1241. http://dx.doi.org/10.1126/science.1078868 |

|

| 23. |

López-Pujol, J., Zhang, F.-M & Ge, S. 2006. Plant biodiversity in China: richly varied, endangered, and in need of conservation. Biodiversity and Conservation 15: 3983–4026. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10531-005-3015-2 |

|

| 24. |

López-Pujol, J., Zhang, F.-M, Sun, H.-Q., Ying, T.-S. & Ge, S. 2011. Centres of plant endemism in China: places for survival or for speciation? Journal of Biogeography 38: 1267–1280. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2699.2011.02504.x |

|

| 25. |

Lu, Y. X., Huang, G. B. & Liang, C. F. 1989. 广西特有植物研究 [Study on the endemic plants from Guangxi]. Guihaia 9: 37–58 [in Chinese]. |

|

| 26. |

Medrano, M., Herrera, C. M. & Barrett, S. C. H. 2005. Herkogamy and mating patterns in the self-compatible daffodil Narcissus longispathus. Annals of Botany 95: 1105–1111. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/aob/mci129 |

|

| 27. |

Mittermeier, R. A., Gil, P. R. & Mittermeier, C. G. 1997. Megadiversity: Earth’s biologically wealthiest nations. Conservation International (CI), Washington, DC. |

|

| 28. |

Myers, N., Mittermeier, R. A., Mittermeier, C. G., da Fonseca, G. A. B, & Kent, J. 2000. Biodiversity hotspots for conservation priorities. Nature 403: 853–858. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/35002501 |

|

| 29. |

Niedenzu, F. 1928. Malpighiaceae. In: Engler, A. (Ed.), Das Pflanzenreich IV. 141. Verlag von Wilhelm Engelmann, Leipzig: 1–870. |

|

| 30. |

Qian, H. 1998. Large-scale biogeographic patterns of vascular plant richness in North America: an analysis at the genera level. Journal of Biogeography 25: 829–836. http://dx.doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2699.1998.00247.x |

|

| 31. |

Qian, H. 2002. A comparison of the taxonomic richness of temperate plants in East Asia and North America. American Journal of Botany 89: 1818–1825. http://dx.doi.org/10.3732/ajb.89.11.1818 |

|

| 32. |

Ren, M. X., Zhang, D. Y. 2004. Herkogamy. In: Zhang, D. Y. (Ed.), 植物生活史进化与繁殖生态学 [Plant life-history evolution and reproductive ecology]. Science Press, Beijing: 302–321 [in Chinese]. |

|

| 33. |

Ren, M.-X., Zhong, Y.-F. & Song, X.-Q. 2013. Mirror-image flowers without buzz pollination in the Asia-endemic Hiptage benghalensis (Malpighiaceae). Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society 173: 764 –774. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/boj.12101 |

|

| 34. |

Sirirugsa, P. 1987. Three new species of Hiptage (Malpighiaceae) in Thailand. Nordic Journal of Botany 7: 277–280. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1756-1051.1987.tb00944.x |

|

| 35. |

Sirirugsa, P. 1991. Malpighiaceae. In: Smitinand, T. & Larsen, K. (Eds.), Flora of Thailand 5(3). The Forest Herbarium, Royal Forest Department, Bangkok: 272–299. |

|

| 36. |

Srivastava, R. C. 1992. Taxonomic revision of the genus Hiptage Gaerlner (Malpighiaceae) in India. Candollea 47: 601–612. |

|

| 37. |

Tang, Z., Wang, Z., Zheng, C. & Fang, J. 2006. Biodiversity in China’s mountains. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment 4: 347–352. http://dx.doi.org/10.1890/1540-9295(2006)004[0347:bicm]2.0.co;2 |

|

| 38. |

Vogel, S. 1990. History of the Malpighiaceae in the light of pollination ecology. Memoirs of the New York Botanical Garden 55: 130–142. |

|

| 39. |

Webb, C. J. & Lloyd, D. G. 1986. The avoidance of interference between the presentation of pollen and stigmas in angiosperms II. Herkogamy. New Zealand Journal of Botany 24: 163–178. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/0028825X.1986.10409726 |

|

| 40. |

Wei, Y.-G., Zhong, S.-H. & Wen, H.-Q. 2004. 广西苦苣苔科植物区系和生态特点研究 [Studies on the flora and ecology Gesneriaceae in Guangxi Province]. Acta Botanica Yunnanica 26: 173–182 [in Chinese]. |

|

| 41. |

Wu, G. & Zhang, Y. 1998. Tibetan plateau forcing and the timing of the monsoon onset over South Asia and the South China Sea. Monthly Weather Review 126: 913–927. http://dx.doi.org/10.1175/1520-0493(1998)126<0913:tpfatt>2.0.co;2 |

|

| 42. |

Ying, T.-S. 1996. 中国种子植物特有属的分布区学研究 [Aerography of the endemic genera of seed plants in China]. Acta Phytotaxonomica Sinica 34: 479–485 [in Chinese]. |

|

| 43. |

Ying, T.-S. 2001. 中国种子植物物种多样性及其分布格局 [Species diversity and distribution pattern of seed plant in China]. Biodiversity Science 9: 393–398 [in Chinese]. |

|

| 44. |

Ying, T. S, Zhang, Y. L. & Boufford, D. E. 1993. The endemic genera of seed plants in China. Science Press, Beijing. |

|

| 45. |

Ying, T.-S. & Zhang, Z.-S. 1984. 中国植物区系中的特有现象–特有属的研究 [Endemism in the flora of China – Studies on the endemic genera]. Acta Phytotaxonomica Sinica 22: 259–268 [in Chinese]. |

|

| 46. |

Zhu, H., Wang, H., Li, B. & Sirirugsa, P. 2003. Biogeography and floristic affinities of the limestone flora in southern Yunnan, China. Annals of Missouri Botanical Garden 90: 444–465. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/3298536 |